New Variant Classes Added to ARUP’s Whole Genome Sequencing Assays Expand Diagnostic Capabilities

Whole Genome Sequencing Transforms Diagnosis and Creates Possibilities for Preventive Care

The Human Genome Project, which was completed in 2003, sequenced the 3 billion base pairs of the human genome over the course of 13 years at a cost of $3 billion, or roughly $1 per base pair. Two decades later, whole genome sequencing (WGS) assays can now sequence an entire human genome in less than a day.

Advances in genomic sequencing technology—increased speed and accessibility and reduced cost—have transformed our ability to identify and understand genetic drivers of disease. WGS facilitates rapid diagnosis, guides timely interventions, and may even offer untapped potential in preventive medicine.

“The field of genomics is really exploding, and that means there is a significant increase in the number of patients that we will be able to diagnose and help with this technology,” said Hunter Best, PhD, FACMG, head of the Molecular Division at ARUP and medical director of Molecular Genetics and Genomics.

Targeted gene panels and assays that sequence the protein-coding regions of the genome, known as whole exome sequencing (WES) assays, have been in clinical use for some time. The exome contains 180,000 exons across 22,300 protein-coding regions, but only comprises 1.5–2% of the entire genome. By comparison, WGS sequences the entire genome, both the coding and noncoding regions, providing a more holistic view of the genetic factors that may cause disease, particularly if a genetic disorder is suspected but the patient’s presentation doesn’t suggest a specific condition.

“As a comprehensive assay, WGS turns up positive variants that otherwise might not have been considered, even by a very experienced genetics provider, due to an atypical presentation,” said Jessica Ponce Hidalgo, PhD, MS, LCGC, genetic counselor lead in Cytogenetics.

In November 2025, ARUP Laboratories added new variant classes to its WGS assays, including copy number variants (CNVs), mitochondrial sequence variants, and SMN1 deletions associated with spinal muscular atrophy.

These additional variant classes have expanded the capabilities of the tests, making it possible to detect more pathogenic variants that may otherwise have been missed.

“There are many different types of large copy number variant-type abnormalities that we can detect with the improved assays,” said Patti Krautscheid, MS, LCGC, supervisor of Genetic Counseling Services at ARUP. “Adding CNV detection makes the tests a one-stop shop for great first-line diagnostic tests.”

Clinical studies have demonstrated that using WGS, especially as a first-line test, can significantly increase the likelihood of diagnosis and improve patient outcomes.

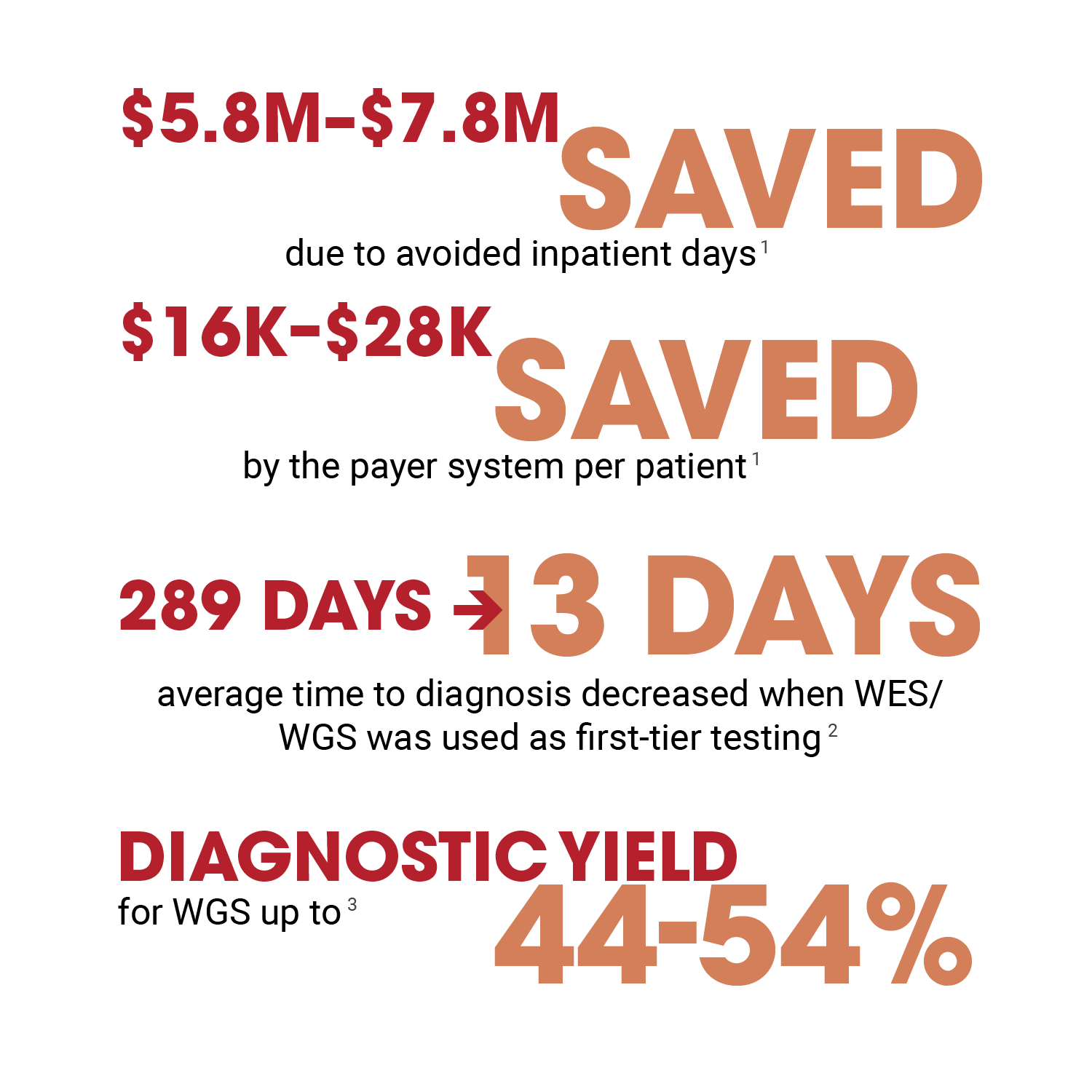

A 2016 study that involved 3,040 cases found that the overall diagnostic yield of WES was 28.8%, whereas a later study cited a yield of 34% for WES. More recent studies have found that the added yield of WGS over WES is 10–20%, Best said.

Not only is WGS more likely to provide a clear diagnosis for patients, but studies have also shown that it can drastically reduce the time it takes to arrive at a diagnosis.

A study to evaluate diagnostic yield and time to precise genetic diagnosis found that 42.3% of pediatric inpatients received a precise genetic diagnosis, and the average time to diagnosis decreased from 289 days to just 13 days, when rapid WES/rapid WGS was used as first-tier testing.

“Without WGS, these patients may go down a whole saga to receive a diagnosis,” Hidalgo said. “It would require multiple tests, multiple blood draws to arrive at a diagnosis. Not only is that not great stewardship, but it increases the stress on patients and the cost of care.”

The strong evidence in support of WGS as a diagnostic tool has led several organizations to develop guidelines that recommend WGS as a first-line test. Most recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published guidelines in July 2025 that recommend WES/WGS as first-line tests for global developmental delay and intellectual disability because of superior diagnostic yield and cost-effectiveness. These guidelines follow similar, previous recommendations from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). The National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) recommends WGS for unexplained epilepsy in individuals of all ages.

The Forefront of Analysis and Interpretation

WGS generates an astonishing amount of data. Each genome sequenced produces approximately 3 million variants. The sheer volume of data creates a monumental task for the individuals who analyze the data for clinically relevant information.

“ARUP is at the forefront of interpretation and analysis,” said Steven Friedman, PhD, ARUP Sequencing and Clinical Analytics director. “Our team of clinical variant scientists is immersed in genetic variant interpretation all day, every day.”

ARUP’s team of highly experienced and qualified clinical variant analysts, clinical variant scientists, and medical directors personally reviews and interprets each case to ensure the information reported is accurate and clinically relevant.

“We provide the highest quality result out there. We manually review the data 100% of the time. There really is no substitute for the years of experience that our team has,” Best said.

ARUP has been performing genetic testing for more than 25 years and was an early adopter of massively parallel sequencing, also known as next generation sequencing.

ARUP’s scientists and medical directors are experts in variant interpretation who regularly contribute to the body of genetics research and knowledge as well as classification determinations. Several members of the team volunteer on the expert panels for ClinGen, a collaborative effort funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to standardize variant classifications. ARUP also contributes to ClinVar, a public database of genetic variants and their clinical relevance. ARUP’s team members leverage their expertise to ensure the most clinically relevant and actionable information is reported.

“Our analysis is very thorough,” said Hidalgo. “We have multiple eyes and various teams reviewing the interpretation and the reports. We provide a lot of detail that other laboratories may not give.”

To facilitate data analysis, ARUP has developed a cutting-edge user interface, known as NGS.web, which incorporates data analysis, data from genetics databases, and reporting tools.

“While we do use tools to aid in filtering data, at the end of the day, our team members perform the interpretation,” Best said. “There’s a lot of nuance in the interpretation of genetic variants, which can be lost when relying solely on AI [artificial intelligence] approaches.”

ARUP teams also align their interpretation with clinical findings to ensure the information provided matches the clinical presentation and is thus the most actionable information.

“The analysis is phenotype driven,” Krautscheid said. “The more robust clinical information providers can supply, the better we can analyze and report those pathogenic variants.”

WGS: An Avenue to Preventive Medicine?

Currently, WGS is used to diagnose patients who present with symptoms that suggest a genetic disorder, but genomic data can also provide information on a patient’s risk for developing conditions later in life, such as hereditary cancer and many other conditions. The genome contains a wealth of information that can be mined to inform those future risks and even prevent complications from developing.

“Many of the health issues that people deal with through their life have a genetic link,” Best said.

For example, individuals may have a genetic predisposition for blood clots that could develop into deep vein thrombosis and become life-threatening. By taking inexpensive medication, patients could avoid a dangerous condition and the associated costs of hospitalization.

“If genomic sequencing is targeted and focused on actionable genetic data, it can do a lot to improve patient outcomes,” Best said. “Genomic sequencing is an incredibly powerful tool in the right clinical scenario. There’s so much information that could be harnessed to support preventive care.”

- Moore C, Arenchild M, Waldman B, et al. Rapid whole-genome sequencing as a first-line test is likely to significantly reduce the cost of acute care in a private payer system. J Appl Lab Med. 2025;10(4):833-842.

- Keefe AC, Scott AA, Kruidenier L, et al. Implementation of first-line rapid genome sequencing in non-critical care pediatric wards. J Pediatr. 2025;286:114699.

- ARUP Laboratories. Genomic sequencing: an evolving standard in molecular genetic diagnosis. Published Sep 2025.